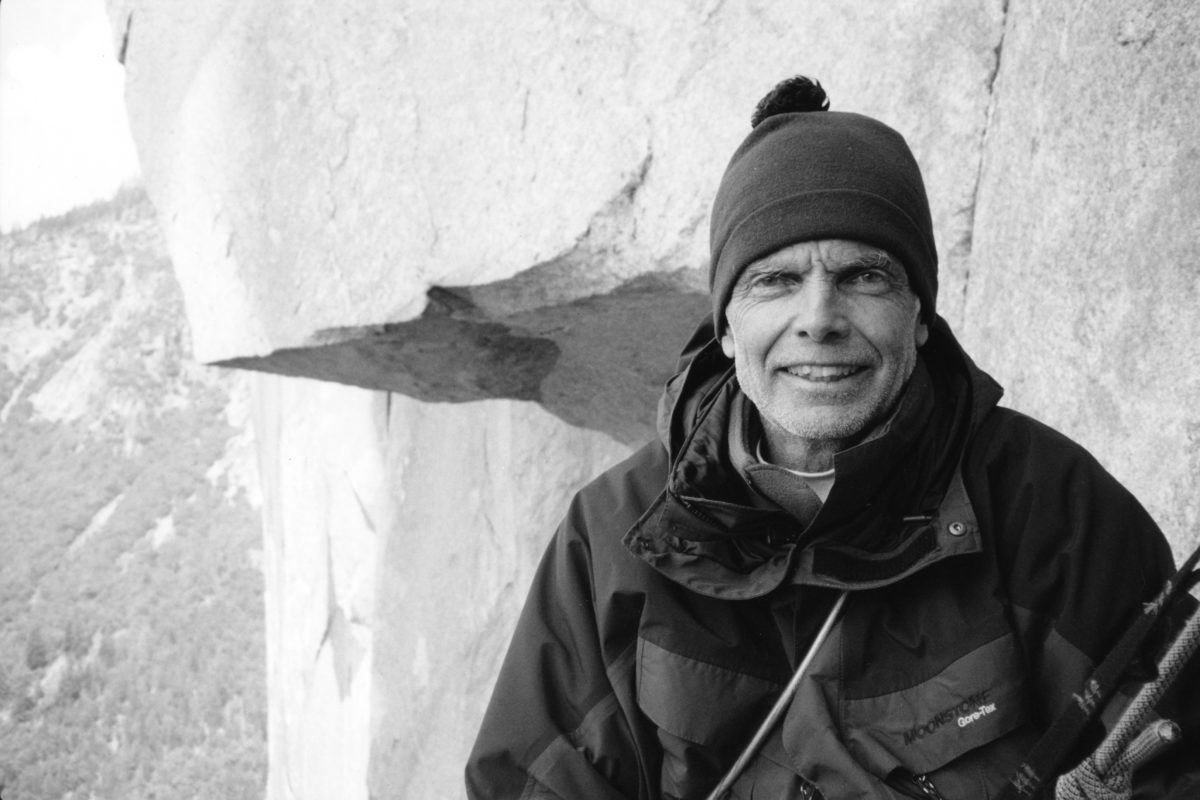

Tom Frost

ABOUT TOM FROST

Tom Frost passed away on Friday, August 24th 2018. Some say he was 81. We believe he was 82 or 83, but Tom certainly never cared about “age.” Tom’s life ended with little pain and was at home by his wife’s side. There is little doubt that somewhere on high, Tom, Jeff Lowe and Royal have been having a great deal of fun since that weekend!

Many consider Tom Frost one of the “Beatles” of rock climbing. With first accents and an eye for photography, Tom chronicled a Golden Era that nobody else managed to capture. As an engineer, his designs and business savvy helped him launch companies that have revolutionized two industries: climbing and photography/cinematography. His environmental ethos is well chronicled and he’s considered a father of “clean climbing.” His ethics and influence led to saving Camp 4 in Yosemite Valley from development and gaining designation on the list of National Historic Places. Before Nepal was a “bucket list” destination, Tom climbed the south face of Annapurna, Kangtega, and Ama Dablam, vacationed with Sherpa and built a hospital and schools with Sir Edmund Hillary.

In the mid-1960’s Tom was recruited by the CIA to participate in a mission in India. The story played out in an Outside Magazine article and a book by Pete Takeda. The Flatlander Team has acquired fascinating new information about the mission(s). Tom took an oath to his country and denied participation. But we know differently…

ROCK CLIMBING AND MOUNTAINEERING

Frost graduated in engineering from Stanford University in 1958 and was a member of the Stanford Alpine Club.[1]

Frost began making first ascents in Yosemite in 1958. In 1960, he made the second ascent of The Nose on El Capitan in Yosemite Valley, a route pioneered by Warren Harding in 1958. He climbed with Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, and Joe Fitschen.

In 1961, Frost and Yvon Chouinard visited the Grand Tetons and made the first ascent of the northeast face of Disappointment Peak, YDS IV, 5.9, A3.[2]

The southwest face of El Capitan from Yosemite Valley. Salathé Wall takes a line up the central part of the face.

On September 12, 1961, Frost, along with Robbins, began the first ascent of the Salathé Wall on El Capitan, named for pioneer Yosemite climber John Salathé. The pair spent two days establishing the first 600 feet of the route and then retreated to the valley floor, where they met up with Chuck Pratt, with whom they spent several more days pushing the route to 1,000 feet above the valley floor. Once again, the climbers descended and resupplied. On September 19, they resumed the climb, and after days of intense vertical aid climbing they reached the Roof, a 15-foot overhang. Using pitons, Frost led this key section of the climb, and on September 24, the trio reached the summit. It had taken them a total of 11 days and 36 pitches of vertical climbing to finish the route, which is rated YDS VI, 5.10, A3.[3]

In 1963, he visited the Himalaya with Edmund Hillary, making the first ascent of Kangtega, and helping with the construction of a school and a hospital for the Sherpas.

From October 22–31, 1964, with Robbins, Pratt and Chouinard, Frost made the first ascent of the North America Wall on El Capitan, YDS VI, 5.8, A5. Robbins described this climb in the 1965 American Alpine Journal: “The nine-day first ascent of the North America Wall in 1964 not only was the first one-push first ascent of an El Capitan climb, but a major breakthrough in other ways. We learned that our minds and bodies never stopped adjusting to the situation. We were able to live and work and sleep in comparative comfort in a vertical environment.” [4] Of this climb, Chris Jones wrote, “For the first time in the history of the sport, Americans lead the world.”[5]

In 1968, Frost visited the Cirque of the Unclimbables in the Northwest Territories of Canada. From August 10 to August 13, along with Jim McCarthy and Sandy Bill, he made the first ascent of the vertical southeast face of the 2,200-foot granite pillar named the Lotus Flower Tower, YDS V, 5.8, A2.[6] This has been called “one of the most aesthetically beautiful rock faces in the world”.[7]

In 1970, he participated in the Annapurna South Face expedition, reaching 25,000 feet.

In 1979, he reached the summit of Ama Dablam on a filming expedition.

In 1986, he returned to Kangtega and climbed a new route with Jeff Lowe.

From 1997 to 2001, he returned to Yosemite big wall climbing with his son Ryan, repeating the Nose, the North America Wall and finally, the Salathé Wall on the 40th anniversary of his first ascent.

NOTABLE FIRST ASCENTS

- 1961 Salathé Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite, CA, USA. Hardest big wall grade VI climb in

- 1961 Salathé Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite, CA, USA. Hardest big wall grade VI climb in world at time of first ascent. With Royal Robbins and Chuck Pratt.[8]

- 1962 Northeast Face, Disappointment Peak, Teton Range, WY. (IV 5.9 A3) FA with Yvon Chouinard.[2]

- 1964 North American Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite Valley – (VI 5.8 A5 3000′) – First Ascent with Royal Robbins, Yvon Chouinard and Chuck Pratt.[9]

PHOTOGRAPHY

Frost photographed many of his first ascents. Glen Denny is himself a mountaineering photographer and author of the book Yosemite in the Sixties. Denny wrote of Frost’s photographic achievements: “Most of the climbing photos you see now are prearranged setups for the camera on much-traveled routes. The impressive thing about Frost is that his classic images were seen, and photographed, during major first ascents. In those awesome situations he led, cleaned, hauled, day after day and–somehow–used his camera with the acuity of a Cartier-Bresson strolling about a piazza. Extremes of heat and cold, storm and high altitude, fear and exhaustion . . . it didn’t matter. He didn’t seem to feel the pressure.” [1]

Several of Frost’s photos were published in Royal Robbins’ book Advanced Rockcraft in 1973.[10] Frost is also an ice climber, and contributed dozens of photographs to Yvon Chouinard’s book Climbing Ice.[11] Nine of his photographs appeared in the book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.[12] Many of his photos appeared in Pat Ament’s Royal Robbins: Spirit of the Age.[13]

In 1979, he co-founded Chimera Photographic Lighting with Gary Regester. The company, based in Boulder, CO, manufactures lighting products for photography and filming. [14]

CLIMBING PHILOSOPHY AND ACTIVISM

Frost is a longtime advocate of environmental ethics in climbing, using natural protection whenever possible, guided by respect for tradition and a desire to “leave no trace.” He articulated his climbing philosophy in an address to an international congress called “The Future of Mountain Sports”, held in Innsbruck, Austria in September, 2002. He opposes what he believes to be excessive use of bolts by sport climbers, especially the altering of traditional climbing routes previously completed without such aids. He criticizes such practices as the result of a desire by some climbers for “instant gratification with little or no accountability.” He opposes five attitudes as the culprits of modern climbing: “selfishness – entitlement – lack of self management – mis-education – and disrespect.”[15]

Frost played a critical role in the fight to save Camp 4 in Yosemite Valley, starting in 1997. He filed a lawsuit against the National Park Service to save the historic rockclimber’s campsite, and convinced the American Alpine Club to support the suit. The effort was successful and Camp 4 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[16]

In 2002, Royal Robbins offered the following description of Frost: “Tom is the kindest and gentlest and most generous person I have ever met, with never an ill word to say of anyone. He is also a man of courage and leadership, as witness his recent vanguard role in the effort to save Camp 4 in Yosemite. And he continues to possess the true spirit of climbing. Just a couple of years ago, at age 60, with his son, he climbed three big El Capitan routes, one of them the North American Wall.”[17]

CLIMBING EQUIPMENT

While working on the first ascent of Kat Pinnacle with Chouinard in 1959, the pair designed and fabricated the Realized Ultimate Reality Piton or RURP, a tiny device that allowed them to finish the most difficult aid climb then completed in North America.[18] This led to a lengthy partnership between Frost and Chouinard in climbing equipment companies such as the Great Pacific Iron Works and Chouinard, Ltd. Frost has described his profession as “piton engineer”.

In the late 1960s, Frost and Chouinard turned their attention to ice climbing and its specialized equipment. They developed an alpine hammer with a drooping pick. Although Austrian climbers had improvised rigid crampons decades before by welding a bar across the hinge of conventional crampons, such devices were not commercially available until 1967. That year, Chouinard and Frost began marketing adjustable rigid crampons made of chrome-molybdenum steel.[19]

Frost and Chouinard invented the climbing protection device called the Hexentric. They applied for a U. S. patent in 1974 and it was granted on April 6, 1976.[20] These are still manufactured by Black Diamond Equipment, which is a successor to earlier companies owned by Frost and Chouinard.

Since 1997, Frost has owned a business manufacturing rock climbing equipment called FROSTWORKS. [21]